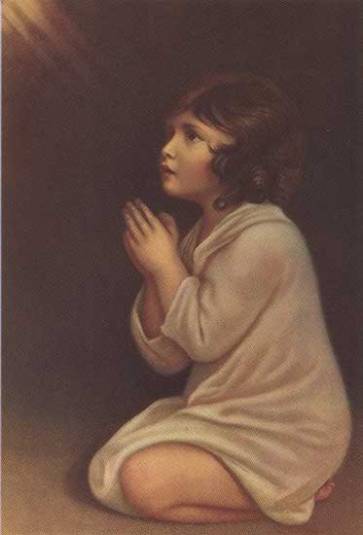

“Speak Lord, for thy servant heareth!”

I was blessed to grow up in a family that loved and honoured the word of God. I vividly remember one evening as a small boy when my dad read to us the story of the call of Samuel. You remember? God begins to call Samuel by name, but Samuel does not recognize God’s voice and thinks it is Eli the priest calling to him. Three times he gets up and reports dutifully to Eli. And on the third time, the penny drops for the old man of God and he instructs the boy to return to his bed and listen. If the Lord should call again, then Samuel is to say (in the old King James that the story book my father was reading quoted): “Speak Lord, for thy servant heareth.”

That night I went to bed feverishly excited. As I put my head on my own pillow, I began to repeat Samuel’s prayer over and over again. “Speak Lord, for thy servant heareth. . . (nothing). . . Speak Lord for they servant heareth. . .” I was disappointed as I went to sleep that night, but looking back on my life, I can see that God has been answering that simple prayer ever since.

Over 30 years later, my desire continues to know God’s word, to hear God’s voice, to experience revelation from God.

Don’t use the ‘R’ word

As a theologian, I’m not supposed to use that word. I am supposed to reserve it for speaking only about Creation, the Incarnation and the Bible. Theologians make a distinction between general revelation, that is, what can be known about God through creation and reason, and special revelation, God’s saving revelation through Christ and inspired Scripture. And a further distinction is made between ‘revelation’ and ‘illumination’—the personal apprehension of what God has already revealed (in creation and the Scriptures). They do this for a very good reason. People these days are not supposed to experience the sort of ‘revelation’ that results in the addition of another testament to the bible or the establishing of a new religion. Agreed. And yet, there are a couple of problems with a strict revelation/illumination divide.

First, the bible (as is so often the case) is not quite so accurate in its usage of the word ‘revelation’ as we theologians might wish. In 1 Corinthians 14, for example, the Corinthians are told to anticipate that ‘revelations’ will frequently occur in the context of church meetings:

What shall we say, brothers? When you come together, everyone has a hymn, or a word of instruction, a revelation, a tongue or an interpretation. All of these must be done for the strengthening of the church. (1 Cor 14:26)

It is astonishing that Paul allows for this even among the Corinthian Church—that disorderly, super-spiritual congregation with so many problems. But even here, the notion of ‘revelation’ is not excluded. Rather, it is merely regulated and made subject to the law of love and the necessity of order.

In another passage, Paul frankly admits that he prays earnestly and ceaselessly that the Ephesian believers would (if you’ll permit me) get a revelation of God’s love:

I keep asking that the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the glorious Father, may give you the Spirit of wisdom and revelation, so that you may know him better. (Eph 1:17)

Apparently, merely hearing the words is not sufficient. And unfortunately, the term ‘illumination’ does not really account for the immediacy and personal. . .ness that is being conveyed here. Its not as if we could know, and all we need is for the ‘light to go on’ as the word implies. The point is that in order to apprehend anything about God we need the revelation of the Holy Spirit, not a mere application of some already-written words to our lives.

And this brings me to the second problem. We cannot see unless our eyes are opened; we cannot hear unless our ears are opened; we cannot properly perceive or apprehend truth unless our mind and heart are opened. And this is the ongoing revelatory (there, I said it again) activity of the Holy Spirit. The Spirit is just as active in my reading of the Bible as he was in inspiring its authors. It is not mere ‘illumination’ as if God only spoke or revealed himself at certain times, and then stopped. When God said “Let there be light.” There was light. And there still is. That word that God spoke so long ago remains both spoken and speaking. The light is still shining. The sun still bears witness to its creator. It is the same with the words of Scripture—they continue to speak, every time that they are read or heard—and indeed with the Word incarnate. Jesus still lives and still speaks. God’s Word remains spoken and speaking. The problem is, not everybody actually listens.

Though everybody hears the voice of creation’s testimony as Romans 1 makes clear, we need revelation in order to apprehend its message. And this should not surprise us. The gospels make clear that while many heard Jesus’ voice during his earthly ministry, comparatively few understood his message; while many beheld his miracles, few apprehended his true identity.

In summary, we need revelation (not just illumination). Paul both prays for believers to experience it, and counsels them in its use to build one another up. This kind of ‘revelation’ is the “I get it!” moment. But, if I may to presume the popular usage of this term—and indeed its biblical usage—over against the theological category which the same word is used to designate, when I actually get something, that is because the Holy Spirit has chosen to reveal it to me at that moment in that way. It is because God loves me infinitely but also individually, and thus knows just how to get through to me. It is not simply because I am slower than others. But Paul’s usage also implies that the ‘revelation’ that I receive about God is not just for me. It has the potential to bless others also and for that reason should be shared.

To be clear, I am not advocating for any ‘revelation’ that would contradict what God has already revealed about himself through the Creation, His Son, and his Word (more on that in my next post). I am trying to rehabilitate the word in its scriptural usage, and share both my hunger and my expectation that God will indeed reveal himself to us.

More on Samuel’s experience next week.